Education Is The Latest Marketing Opportunity In Japan

Japan is a highly developed country and one of the economic powerhouses of East Asia. In fact, the country ranks among the world leaders based on several different economic and social metrics. As such, you would assume that Japan has a highly developed education system to match.

And this is true, at least to an extent. Japan’s educational infrastructure, levels of investment, and teaching standards are all extremely advanced. For example, in Japan, over 50% of adults have completed some form of further education after high school, which puts the East Asian nation in second place for this particular list. However, in other areas, Japan lags behind — it is this slowing of performance in some areas that is fueling changes in policy and providing opportunities for investment from all over the world.

Here’s a look at the key factors driving opportunities designed to help Japan craft a formidable education system for future generations.

COVID-19 and related challenges

COVID-19 has offered an advantage as well as a challenge for Japanese educators, driving them toward remote classroom structures and digital learning technologies. This is a crucial opportunity for the right investor to market and deliver innovative products that make remote learning easier.

The Japanese educational system

Japanese children must undergo nine years of compulsory education, which begins when they are six years old. Between the ages of six and 12, they are in the Primary phase of their education, followed by Secondary education from ages 12 to 15. At 15, the student may decide to enter a vocational school for one year, a college of technology for five years, or continue their secondary education in a high school for three years. Or, they may decide to leave the schooling system at this point.

Education has been this way, more or less, since the end of the Second World War and has served Japan well in the second half of the 20th century. However, some of the poor performance in recent years has been blamed on this rigid structure, paving the way for increased innovation and investment.

This may include innovative ways to deliver information to youngsters at different stages of their development — through interactive learning software, for example. Alternatively, this may involve a shake-up of the curriculum and the introduction of subjects such as coding and web development.

Education spending

While Japan is in 13th place for its teacher salaries, the country ranks somewhat higher in terms of investment and spending on tertiary education. Each year, $19,289 is spent per student in tertiary education, the seventh-highest spend in the world, after that of Australia, Norway, Sweden, the UK, the US, and Luxembourg.

However, when looking at primary education spend per student, Japan drops to 12th place globally. For secondary education spend alone, they are 13th, and they rank 13th in the world for early childhood spend per student. Viewed as a whole, from primary to the end of secondary education, Japan’s per-student spend is the 14th highest in the world, leaving some room for improvement. If investment increases to plug this gap, this translates to increased opportunities for marketers in Japan’s education sector.

Changes to Japan’s demographics

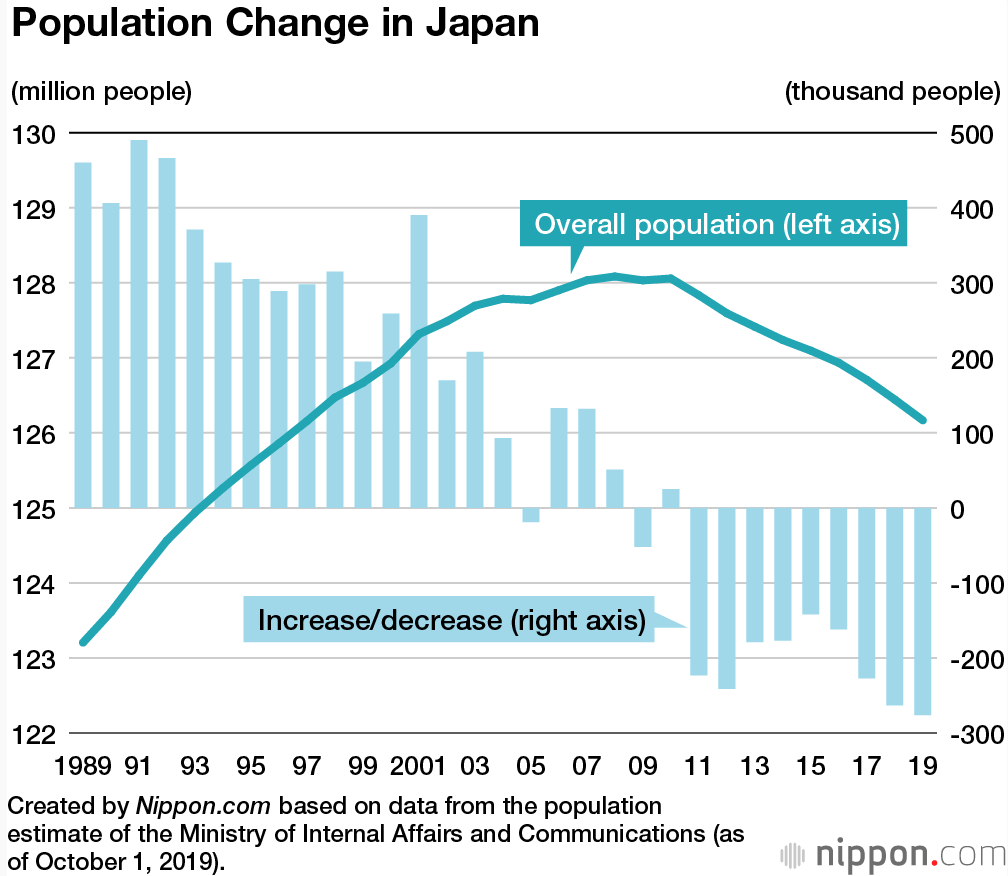

As Japan’s population falls and the average age of its citizens increases, cracks are beginning to form in the education system.

Source: https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h00705/

This is another element that could lead to a reshuffle of education in Japan, as efforts are made to bring the education system more in line with the needs of an aging population and changing demographics. While this presents a challenge for Japan, it also represents a potential opportunity for investors.

Women in Japan

Women in the Japanese workforce

The employment rate for university-educated women reached 79% in 2017, and in 2018, 44.1% of Japan’s entire labor force was comprised of women. This is thanks in part to government intervention — alarmed by the aging population of Japan and the dwindling workforce, the government has repeatedly encouraged the entry of women across a range of industries.

However, of these women, around 44.2% are employed in part-time and temporary roles, many of which are low paying. This can make providing for a family difficult.

The implications this has for investment in education are two-fold. On the one hand, Japan is moving away from traditional models of a male breadwinner and a stay-at-home mother. This means education must become more flexible if it is to meet the diverse needs of this new type of family. On the other hand, as we have seen, the jobs market has not yet caught up to these new generations of liberated women, and gender inequality still exists in terms of payment and conditions. With this in mind, innovation and investment need to make education more affordable and more convenient.

Attitudes to education

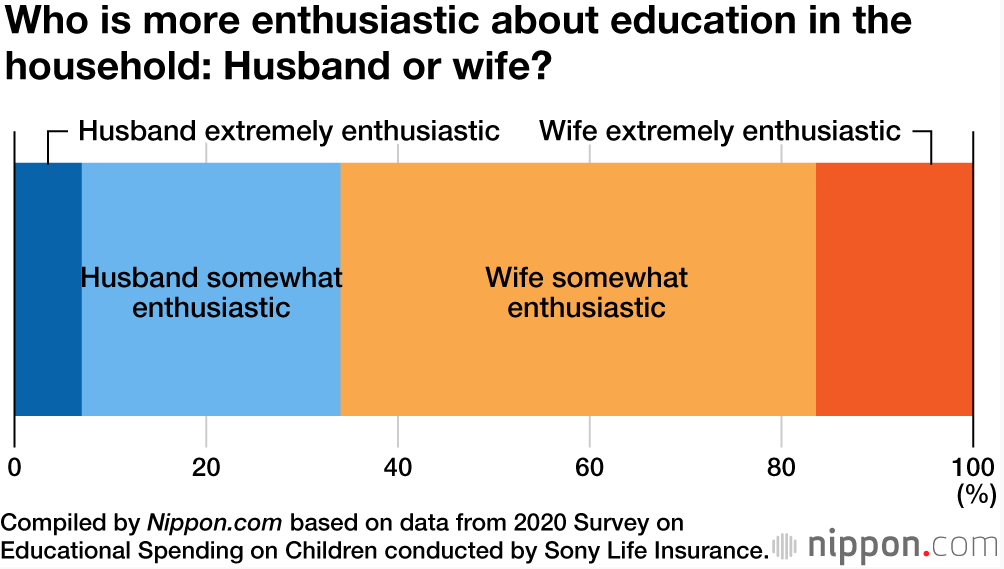

According to data released by Nippon.com in 2020, Japanese wives are more enthusiastic about education than their husbands — 66% of couples said the wife was either extremely or somewhat enthusiastic.

Source: https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h00688/survey-finds-majority-of-japanese-parents-view-money-as-determining-educational-success.html

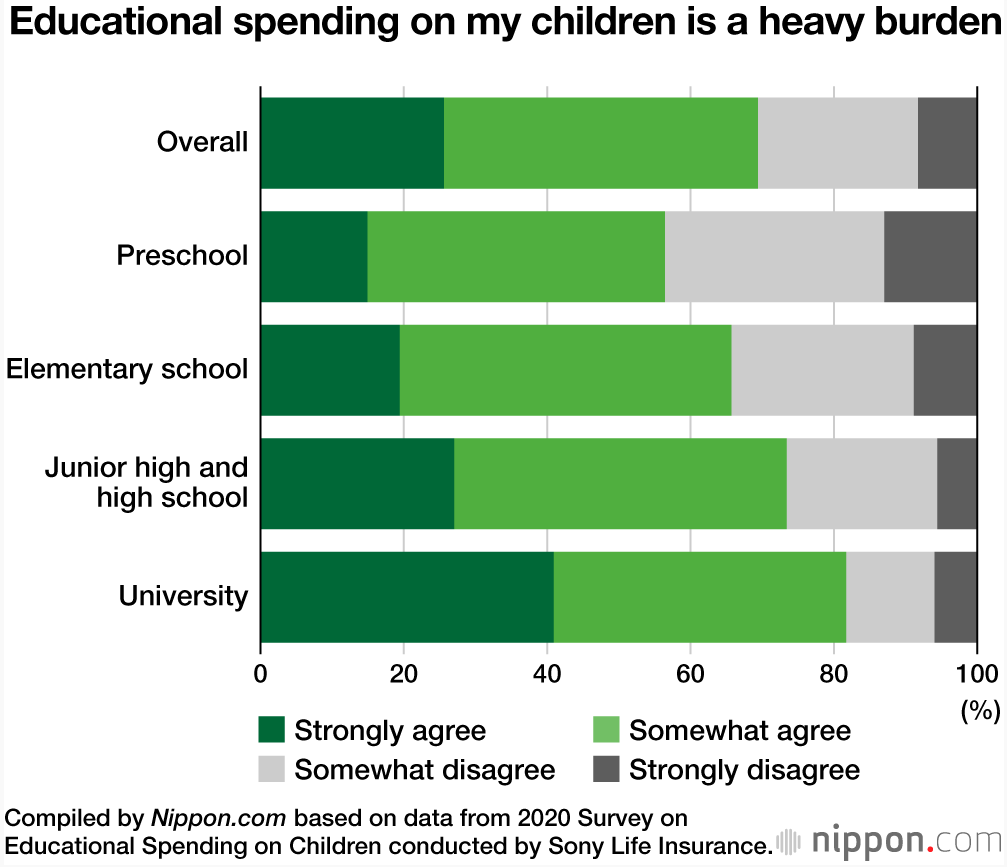

This is an interesting figure (below), as it appears that significant numbers of parents now consider their children’s education to be “a heavy financial burden.” More than 25% of parents said they strongly agreed with this statement during junior high and high school education, rising to 41% with regard to university education. For most parents, weighing the capital spend against eventual financial remuneration following graduation is the main indicator of success in education.

Source: https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h00688/survey-finds-majority-of-japanese-parents-view-money-as-determining-educational-success.html

This demonstrates that the appetite for spending on education still exists within Japan. The market remains ripe for marketers to make significant gains while supporting Japanese families and young people.

Japanese Education in Comparison to Other OECD Countries

As touched on above, there are several inconsistencies in Japan’s educational performance. For example, 62% of 25- to 34-year-olds have a bachelors’ degree or higher, compared to 45% across the OECD group. Japan’s investment in education across the primary to tertiary levels is 4% of GDP, 0.9% less than the average across OECD countries, while the percentage of upper secondary students who enroll in VET programs is also below the OECD average.

Also worrying, in a society that has worked so hard to drive women into the workplace, the number of women graduating from doctoral programs is far behind that of other OECD nations. This could lead to an increasing disparity between the earning power of men and women in the workforce, despite women making up almost half of this workforce.

Key Takeaways: A Marketing Opportunity

So what does all this mean for investors and marketers? Let’s look at some of the key takeaways that help us better understand the investment opportunity in Japan.

- Japan’s GDP is one of the highest in the world. The nation’s society leads the world in many different fields — this is a country that expects a great deal.

- While Japan’s population is shrinking, the increasing education spending across the country provides great opportunities for marketers and entrepreneurs looking to expand in this area.

- According to a number of key metrics, Japan lags behind other OECDs on the education front. To combat this, the government is working to make future-focused skills such as computing and coding mandatory in Japanese schools, opening the door to innovation and investment.

- There are also drives to develop English as a second language within Japanese schools, making its education system more international in the process and providing opportunities for international investors.

- The stage is set for huge shifts in terms of education policies and approaches, as well as for high levels of investment.

Make the Most of Marketing Opportunities in Japan

To understand more about how your business can achieve success through marketing and development in Japan, reach out to the Principle team today.

About Principle

Principle helps businesses of all sizes make better decisions through data. For the better part of a decade, we have helped global brands and Fortune 500 companies turn data into intelligence and actionable insights they can use in digital marketing.

Our team of 100 employees includes experts across Analytics, Paid Marketing, SEO, and Data Visualization. We offer actionable and measurable data analytics strategies, SEO, and campaign management services that deliver the digital transformation your business needs to outperform the competition.

We recruit independent professionals who have their own personality, an established way of life, a unique skill, and can share our philosophy. With such colleagues, we believe that individuals and companies will grow together and achieve great quality and result in an unseen business world.

To learn more about digital marketing and advertising in Japan or elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific region, feel free to contact us at Principle.

Want to grow your business in Asia?

Principle is a data-driven marketing agency that grows your business in Japan and the rest of the Asia Pacific market. Click here to learn more about our digital marketing services for the APAC region.